Introduction to Weapons Systems and Political Stability: A History

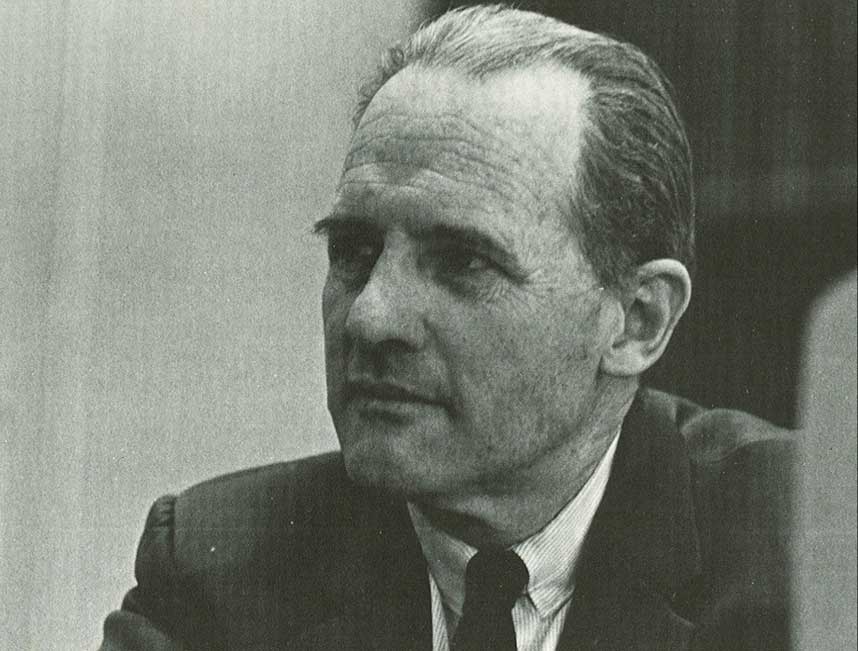

by Carroll Quigley

The full PDF ebook of the 1983 first edition of Weapons Systems and Political Stability: A History can be downloaded from the official Carroll Quigley Website.

Jump to section within Introduction:

1. The Human Condition and Security

The earliest moments of my day are divided about equally between the morning newspaper and the cat. At six a.m., as I cautiously open the front door to get the paper from the porch, my mind is concerned with achieving my purpose as unobtrusively as possible. I am not yet prepared to be seen by my neighbors, and, accordingly, I open the door hardly more than a foot. But that is enough for the cat, who has been patiently awaiting my appearance. It slips silently through the opening, moves swiftly to the center of the living room and pauses there to emit a peremptory “meow.” The cry tells, as plainly as words, of its need for food, so I must put my paper down to follow its jaunty waving tail to the kitchen to get its morning meal of cod fillet from the refrigerator.

While the cat daintily mouths its fish in the kitchen, I return to my paper in the living room, but have hardly grasped the world news on the front page before the cat is back, rubbing its arched back against my leg and purring noisily in the early morning quiet. By the time I have turned to page two, the cat, still purring, has jumped lightly to the sofa and is settling down to its daylong nap. Within minutes, it is sprawled in complete relaxation, while my own nervous system, spurred up by the violence and sordid chaos of the news, is tensing to the day’s activities.

The contrast between the simple pattern, based on simple needs, of the cat’s life and the activities of men as reflected in the daily press, makes me, for brief moments, almost despair of man’s future. The cat’s needs are few and simple. They hardly extend beyond a minimal need for physical exercise, which includes a need for food, some expression of the reproductive urge, a need for some degree of physical shelter and comfort in which to rest. We could list these needs under the three headings of food, sex, and shelter.

No such enumeration of man’s needs could be made, even after long study. Man has the basic needs we have listed for the cat, but in quite different degrees and complexity. In addition, man has other, and frequently contradictory, needs. For example, man has the need for novelty and escape from boredom, but, at the same time, he has a much more dominant and more pervasive need for the security of established relationships. Only from such established patterns of relationships, covering at least a portion of his needs, can man successfully strike out on paths of novelty to create new relationships able to satisfy other needs, including the need for novelty. Surely man has social needs for relationships with other humans, relationships which will provide him with emotional expression, with companionship or love. No man can function as a cat operates in its narrower sphere of activities unless he feels that he is needed, is admired, is loved, or, at least, is noticed by other humans.

Even less tangible than these emotional needs of man’s social relationships are needs which man has for some kind of picture of his relationship with the universe as a whole. He has to have explanations of what happens. These need not be correct or true explanations; they need only to be satisfying, at least temporarily, to man’s need for answers to his questions of “how?” and “why?” the universe acts the way it seems to act. This search for “how” and especially for “why” is particularly urgent with reference to his own experiences and future fate. Why does he fail in so many of his efforts? Why are his needs for companionship and love so frequently frustrated? Why does he grow older and less capable? Why does he sicken and die?

As a biological organism functioning in a complex universe which he does not understand, man may be regarded as a bundle of innumerable needs of very different qualities and of a great variety of degrees of urgency. It would be quite impossible to organize these needs into three or even four categories, as we did with the cat, but we could perhaps, in a rough fashion, divide them into a half dozen or more groups or classes of needs. If we do this, we shall find that they include: (1) man’s basic material needs usually listed as food, clothing, and shelter; (2) the whole group of needs associated with sex, reproduction, and bringing up the young; (3) the immense variety of relationships which seek to satisfy man’s need for companionship and emotional relationships with his fellow men; and (4) the need for explanation which will satisfy his questions about “how?” And “why?”

Yet certainly these four do not exhaust the range of man’s needs, for none of these can be enjoyed unless man can find intervals in which he is not struggling to preserve his personal safety. Food, sex, companionship, and explanation must all wait when man’s personal existence is in jeopardy and must be satisfied in those intervals when he has security from such jeopardy. Thus the need for security is the most fundamental and most necessary of human needs, even if it is not the most important.

The last statement is more acceptable to a reader today that it would have been fifty years ago because, in the happier political situation of that now remote period, security was not considered of primary significance and was not regarded as comparable with men’s economic or personal needs. That blindness, for such it was, arose from the peculiar fact that America a generation ago had had political security for so long a time that this most essential of needs had come to be taken for granted and was hardly recognized as a need at all, certainly not as an important one. Today the tide of opinion has changed so drastically that many persons regard security as the most important of all questions. This is hardly less mistaken, for security is never important: it is only necessary.

The inability of most of us to distinguish between what is necessary and what is important is another example of the way in which one’s immediate personal experience, and especially the narrow and limited character of most personal experience, distorts one’s vision of reality. For necessary things are only important when they are lacking, and are quickly forgotten when they are in adequate supply. Certainly the most basic of human needs are those required for man’s continued physical survival and, of those, the most constantly needed is oxygen. Yet we almost never think of this, simply because it is almost never lacking. Yet cut off our supply of oxygen, even for a few seconds, and oxygen becomes the most important thing in the world. The same is true of the other parameters of our physical survival such as space and time. They are always necessary, but they become important only when we do not have them. This is true, for example, of food and water. It is equally true of security, for security is almost as closely related to mere physical survival as oxygen, food, or water.

The less concrete human needs, such as those for explanation and companionship are, on the other hand, less necessary (at least for mere survival) but are always important, whether we have them or lack them. In fact, the scale of human needs as we have hinted a moment ago, forms a hierarchy seven or eight levels high, ranging from the more concrete to the less concrete (and thus more abstract) aspects of reality. We cannot easily force the multi-dimensional complexities of reality and human experience into a single one-dimensional scale, but, if we are willing to excuse the inevitable distortion arising from an effort to do this, we might range human needs from the bottom to the top, on the levels of (1) physical survival; (2) security; (3) economic needs; (4) sex and reproduction; (5) gregarious needs for companionship and love; (6) the need for meaning and purpose; (7) the need for explanation of the functioning of the universe. This hierarchy undoubtedly reflects the fact that man’s nature itself is a hierarchy, corresponding to his hierarchy of needs, although we usually conceal the hierarchical nature of man by polarizing it into some kind of dualistic system, such as mind and body, or, perhaps, by dividing it into the three levels of body, emotions, and intellect.

In general terms, we might say that the hierarchy for human needs, reflecting the hierarchy of human nature, is also a hierarchy ranging from necessary needs to important needs. The same range seems to reflect the evolutionary development of man, from a merely animal origin, through a gregarious ape-like creature, to the more rational and autonomous creature of human history. In his range of needs, reflecting thus both his past evolution and his complex nature, are a bundle of survivals from that evolutionary process. The same range is also a kind of hierarchy from necessary things (associated more closely with his original animal nature) to important things (associated more closely with his more human nature). In this range the need for security, which is the one that concerns us now, is one of the most fundamental and is, thus, closer to the necessity end of the scale. This means that it is a constant need but is important only when we do not have it (or believe we do not have it). That is why the United States, in the 1920s and 1930s, could have such mistaken ideas about the relative significance of security and prosperity. Because we had had the former, with little or no effort or expense to ourselves, from about 1817 to at least 1918, we continued to regard this almost essential feature of human life as of less significance than prosperity and rising standards of living from 1920 until late in the 1930s or even to 1941. Accordingly, we ignored the problem of security and concentrated on the pursuit of wealth and other things we did not have. This was a perfectly legitimate attitude toward life, for ourselves, but it did not entitle us to insist that other countries, so much closer to the dangers of normal human life than we were, must accept our erroneous belief that economics was more fundamental than politics and security.

Many years ago, when I talked of this matter to my students, all in uniform and preparing to go off to fight Hitler, one of them, who already had a doctorate degree in economics, challenged my view that politics is more fundamental than economics. The problem arose from a discussion of the Nazi slogan “Guns or butter?” I asked him, “If you and I were together in a locked room with a sub-machine gun on one side and a million dollars on the other side, and you were given the first choice, which of these objects would you choose?” He answered, “I would take the million dollars.” When I asked, “Why?,” he replied, “Because anyone would sell the gun for a lot less than a million dollars.” “You don’t know me,” I retorted, “because if I got the gun, I’d leave the room with the money as well!”

This rather silly interchange is of some significance because the student’s attitude is about buying the gun with some fraction of the money assumes a structure of law and order under which commercial agreements are peaceful, final, and binding. He is like the man who never thinks of oxygen until it is cut off; he never thinks of security because he has always had it. At the time I thought it was a very naive frame of mind with which to go to war with the Nazis, who chose guns over butter because they knew that the possession of guns would allow them to take butter from their neighbors, like Denmark, who had it.

In recent years there has been a fair amount of unproductive controversy about the real nature of man and what may be his real human needs. In most cases, these discussions have not gotten very far because the participants have generally been talking in groups which are already largely in agreement, and they have not been carrying on any real dialogue across lines of basic disagreement. Accordingly, each group has simply rejected the views most antithetical to its own assumptions, with little effort to resolve areas of acute contradiction. There are, however, some points on which there could hardly be much disagreement. These include two basic facts about human life as we see it being lived everywhere. These are: (1) Each individual is an independent person with a will of his own and capable of making his own decisions; and (2) Most human needs can be satisfied only by cooperation with other persons. The interaction of these two fundamental facts forms the basis for most social problems.

If each individual has his own autonomous will making its own decisions, there will inevitably be numerous clashes of conflicting wills. There would be no need to reconcile these clashes if individuals were able to satisfy their needs as independent individuals. But there are almost no needs, beyond those for space, time, oxygen, and physiological elimination, which can be satisfied by man in isolation. The great mass of human needs, especially those important ones which make men distinctively human, can be satisfied only through cooperative relationships with other humans. As a consequence, it is imperative that men work out patterns of relationships on a cooperative basis which will minimize the conflicts of individual wills and allow their cooperative needs to be satisfied. From these customary cooperative relationships emerge the organizational features of the communities of men which are the fundamental units of social living.

Any community of persons consists of the land on which they are, the people who make it up, the artifacts which they have made to help them in satisfying their needs, and, above all, the patterns of actions, feelings, and thoughts which exist among them in relationships among persons and between persons and artifacts. These patterns may be regarded as the organization of the people and the artifacts on the terrain. The organization, with the artifacts but without the people as physical beings, is often called the “culture” of the community. Thus we might express it in this way:

- 1. Community = people + artifacts + patterns of thoughts, feelings and actions

- 2. Community = people + culture

- 3. Community = people + artifacts + organization.

The significance of these relationships will appear later, but one very important one closely related to the major purpose of this book may be mentioned here.

When two communities are in conflict, each trying to impose its will on the other, this can be achieved if the organization of one can be destroyed so that it is no longer able to resist the will of the other. That means that the purpose of their conflict will be to destroy the organization but leave the people and artifacts remaining, except to the degree that these are destroyed incidentally in the process of disrupting their organization in order to reduce their capacity to resist. In European history, with its industrialized cities, complex division of labor, and dense population, the efforts to disrupt organization have led to weapons systems of mass destruction of people and artifacts, which could, in fact, so disrupt European industrial society, that the will to resist is eventually destroyed. But these same weapons, applied to a different geographical and social context, such as the jungles of southeast Asia, may not disrupt their patterns sufficiently to lower their wills to resist to the point where the people are willing to submit their wills to those of Western communities; rather they may be forced to abandon forms of organization which are susceptible to disruption by Western weapons for quite different and dispersed forms of organization on which Western weapons are relatively ineffective. This is what seems to have happened in Vietnam, where the Viet Cong organizational patterns were so unfamiliar to American experience that we had great difficulty in recognizing their effectiveness or even their existence, except as the resistance of individual people. As a result, we killed these people as individuals without disrupting their Viet Cong organization, which we ignored because it was not similar to what we recognized as an organization of political life in Western eyes, and, for years, we deceived ourselves that we were defeating the Viet Cong organization because we were killing people and increasing our count of dead bodies (the majority of whom certainly formed no part of the Viet Cong organization which was resisting our will).

The importance of organization in satisfying the human need for security is obvious. No individual can be secure alone, simply from the fact that a man must sleep, and a single man asleep in the jungle is not secure. While some men sleep, others must watch. In the days of the cave men, some slept while others kept up the fire which guarded the mouth of the cave. Such an arrangement for sleeping in turns is a basic pattern of organization in group life, by which a number of men cooperate to increase their joint security. But such an organization also requires that each must, to some degree, subordinate his will as an individual to the common advantage of the group. This means that there must be some way in which conflicts of wills within the group may be resolved without disrupting the ability of their common organization to provide security against any threat from outside.

These two things—the settlement of disputes involving clashes of wills within the group and the defense of the group against outside threats—are the essential parts of the provision of security through group life. They form the opposite sides of all political life and provide the most fundamental areas in which power operates in any group or community. Both are concerned with clashes of wills, the one with such clashes between individuals or lesser groups within the community and the other with clashes between the wills of different communities regarded as entities. Thus clashes of wills are the chief problems of political life, and the methods by which these clashes are resolved depend on power, which is the very substance of political action.

All of this is very elementary, but contemporary life is now so complicated and each individual is now so deeply involved in his own special activities that the elementary facts of life are frequently lost, even by those who are assumed to be most expert in that topic. This particular elementary fact may be stated thus: politics is concerned with the resolution of conflicts of wills, both within and between communities, a process which takes place by the exercise of power.

This simple sentence covers some of the most complex of human relationships, and some of the most misunderstood. Any adequate explanation of it would require many volumes of words and, what is even more important, several lifetimes of varied experience. The experience would have to be diverse because the way in which power operates is so different from one community to another that it is often impossible for an individual in one community and familiar with his own community’s processes for the exercise of power to understand, or even to see, the processes which are operating in another community. Much of the most fundamental differences are in the minds and neurological systems of the persons themselves, including their value systems which they acquired as they grew up in their own communities. Such a value system establishes priorities of needs and limits of acceptance which are often quite inexplicable to members of a different community brought up in a different tradition. Since human beings can be brought up to believe almost anything or to put up with almost anything, the possible ways in which the political life of any community can be organized are almost limitless.

In our own tradition, the power which resolves conflicts of wills is generally made up of three elements. These are force, wealth, and ideology. In a sense, we might say that we resolve conflicts of wills by threatening or using physical force to destroy capacity to resist: or we use wealth to buy or bribe consent; or we persuade an opponent to yield by arguments based on beliefs. We are so convinced that these three make up power that we use them even in situations where different communities with quite different traditions of the nature of power are resisting. And as a result, we often mistake what is going on in such a clash of communities with quite different traditions of power. For example, in recent centuries, our Western culture has had numerous clashes with communities of Asiatic or African traditions whose understanding of power is quite different from our own, since it is based on religious and social considerations rather than on military, economic, or ideological, as ours is.

The social element in political power rests on the human need to be a member of a group and on the individual’s readiness to make sacrifices of his own desires in order to remain a member of such a group. It is largely a matter of reciprocity, that individuals mutually restrain their individual wills in order to remain members of a group, which is necessary to satisfy man’s gregarious needs. It is similar to the fact that individuals accept the rules of a game in order to participate in the game itself. This was always the most important aspect of power in Chinese and other societies, especially in Africa, but it has been relatively weak in others, such as our Western society or in Arabic culture of the Near East. The religious element was once very important in our own culture, but has become less so over the past five centuries until today it is of little influence in political power, although it is still very important in forming the framework of power in other areas, most notably in traditional Tibet, and in many cultures of Asia and Africa.

The inability of persons from one culture to see what is happening in another culture, even when it occurs before their eyes, is most frequent in matters of this kind, concerned with power. Early English visitors to Africa found it quite impossible to understand an African war, even when they were present at a “battle.” In such an encounter, two tribes lined up in two opposing lines, each warrior attired in a fantastic display of fur, feathers, and paint. The two armies danced, sang, shouted, exchanged insults, and gradually worked themselves up into a state in which they began to hurl their spears at each other. A few individuals were hit and fell to the ground, at which point one side broke and ran away, to the great disgust of the observing English. The latter, who hardly can get themselves to a fighting pitch until after they have suffered casualties or lost a battle or two, considered the natives to be cowardly when they left the field in flight after a few casualties. What they did not realize was that the event which they saw was not really a battle in the sense of a clash of force at all, but was rather an opportunity for a symbolic determination of how the spiritual forces of the world viewed the dispute and indicated their disfavor by allowing casualties on the side upholding the wrong view. The whole incident was much more like a European medieval judicial trial by ordeal, which also permitted the deity to signify which side of a dispute was wrong, than it was to a modern English battle.

In the most general terms we might say that men live in communities in order to seek to satisfy their needs by cooperation. These needs are so varied, from the wide range of human needs based on man’s long evolutionary heritage, that human communities are bound to be complex. Such a community exists in a matrix of five dimensions, of which three dimensions are in space, the fourth is the dimension of time, and the fifth, which I shall call the dimension of abstraction, covers the range of human needs as developed over the long experience of past evolution. This dimension of abstraction for purposes of discussion will be divided into six or more aspects or levels of human experience and needs. These six are military, political, economic, social, religious, and intellectual. If we want a more concise view of the patterns of any community, we might reduce these six to only three, which I shall call: the patterns of power; the patterns of wealth; and the patterns of outlook. On the other hand, it may sometimes be helpful to examine some part of human activities in more detail by subdividing any one of these levels into sub-levels of narrower aspects to whatever degree of specific detail is most helpful.

In such a matrix, it is evident that the patterns of power may be made up of activities on any level or any combination of sub-levels. Today, in our Western culture we can deal with power adequately in terms of force, wealth, and ideology, but in earlier history or in other societies, it will be necessary to think of power in quite different terms, especially social and religious, which are no longer very significant to our own culture. The great divide, which shunted our culture off in directions so different from those which dominate the cultures of much of Asia and Africa down to the present, occurred about the sixth century B.C., so if we go back into our own historical background before that, we shall have to deal with patterns closer to modern Asia or Africa than our own contemporary culture.

⤴️RETURN TO TOP

2. Security and Power

Just as our ideas on the nature of security are falsified by our limited experience as Americans, so our ideas are falsified by the fact that we have experienced security in the form of public authority and the modern state. We do not easily see that the state, especially in its modern sovereign form, is a rather recent innovation in the experience of Western civilization, not over a few centuries old. But men have experienced security and insecurity throughout all human history. In all that long period, security has been associated with power relationships and is today associated with the state only because this is the dominant form which power relationships happen to take in recent times. But even today, power relationships exist quite outside of the sphere of the state, and, as we go farther into the past, such non-state (and ultimately, non-public) power relationships become more dominant in human life. For thousands of years, every person has been a nexus of emotional relationships, and, at the same time, he has been a nexus of economic relationships. In fact, these may be the same relationships which we look at from different points of view and regard them in the one case as emotional and in another case as economic. These same relationships, or other ones, form about each person a nexus of power relationships.

In the remote past, when all relationships through which a person expressed his life’s energies and obtained satisfaction of his human needs were much simpler than today, they were all private, personal, and fairly specific relationships. Now that some of these relationships, from the power point of view, have been rearranged and have become, to a great extent, public, impersonal, and abstract, we must not allow these changes to mislead us about their true nature or about the all-pervasive character of power in human affairs, especially in its ability to satisfy each person’s need for security.

The two problems which we face in this section are: what is the nature of power? And, what is the relationship between power and security? Other questions, such as how power operates or how power structures change in human societies, will require our attention later.

Power is simply the ability to obtain the acquiescence of another person’s will. Sometimes this is worded to read that power is the ability to obtain obedience, but this is a much higher level of power relationship. Such relationships may operate on many levels, but we could divide these into three. On the highest level is the ability to obtain full cooperation. On a somewhat lower level is obedience to specific orders, while, still lower, is simple acquiescence, which is hardly more than tacit permission to act without interference. All of these are power relationships which differ simply in the degree and kind of power needed to obtain them.

The power to which we refer here is itself complex and can be analyzed, in our society, into three aspects: (1) force; (2) wealth; and (3) persuasion. The first of these is the most fundamental (and becoming more so) in our society, and will be discussed at length later. The second is quite obvious, since it involves no more than the purchase or bribery of another’s acquiescence, but the third is usually misunderstood in our day.

The economic factor enters into the power nexus when a person’s will yields to some kind of economic consideration, even if this is merely one of reciprocity. When primitive tribes tacitly hunt in restricted areas which do not overlap, there is a power relationship on the lowest level of economic reciprocity. Such a relationship may exist even among animals. Two bears who approach a laden blueberry bush will eat berries from opposite sides of the bush without interfering with each other, in tacit understanding that, if either tried to dispossess the other, the effort would give rise to turmoil of conflicting force which would make enjoyment of the berries by either impossible. This is a power relationship based on economic reciprocity, and it will break down into conflict unless there is tacit mutual understanding as to where the dividing lines between their respective areas of operation lie. This significant subjective factor will be discussed later.

The ideological factor in power relationships, which I have called persuasion, operates through a process which is frequently misunderstood. It does not consist of an effort to get someone else to adopt our point of view or to believe something they had not previously believed, but rather consists of showing them that their existing beliefs require that they should do what we want. This is a point which has been consistently missed by the propaganda agencies of the United States government and is why such agencies have been so woefully unsuccessful despite expenditures of billions of dollars. Of course it requires arguing from the opponent’s point of view, something Americans can rarely get themselves to do because they will rarely bother to discover what the opponent’s point of view is. The active use of such persuasion is called propaganda and, as practiced, is often futile because of a failure to see that the task has nothing to do directly with changing their ideas, but is concerned with getting them to recognize the compatibility between their ideas and our actions. Propaganda also has another function which will be mentioned later and which helps to explain how the confusion just mentioned arose.

On its highest level the ideological element in power becomes a question of morale. This is of the greatest importance in any power situation. It means that the actor himself is convinced of the correctness and inevitability of his actions to the degree that his conviction serves both to help him to act more successfully and to persuade the opposition that his (the actor’s) actions are in accordance with the way things should be. Strangely enough, this factor of morale, which we might like to reserve for men because of its spiritual or subjective quality, also operates among animals. A small bird will often be observed in summer successfully driving a crow or even a hawk away from its nest, and a dog who would not ordinarily fight at all will attack, often successfully, a much larger beast who intrudes onto his front steps or yard. This element of subjective conviction which we call morale is the most significant aspect of the ideological element in power relationships and shows the intimate relationship between the various elements of power from the way in which it strengthens both force and persuasion.

It also shows something else which contemporary thinkers are very reluctant to accept. That is the operation of natural law. For the fact that animals recognize the prescriptive rights of property, as shown in the fact that a much stronger beast will yield to a much weaker one on the latter’s home area, or that a hawk will allow a flycatcher to chase it from the area of the flycatcher’s nest, shows a recognition of property rights which implies a system of law among beasts. In fact, the singing of a bird (which is not for the edification of man or to attract a mate, but is a proclamation of a residence area to attract other birds of the same habits) is another example of the recognition of rights and thus of law among non-human life.

Of course, in any power situation the most obvious element to people of our culture is force. This refers to the simple fact of physical compulsion, but it is made more complicated by the two facts that man has, throughout history, modified and increased his physical ability to compel, both by the use of tools (weapons) and by organization of numerous men to increase their physical impact. It is also confused, for many people, by the fact that such physical compulsion is usually aimed at a subjective target: the will of another person. This last point, like the role of morale already mentioned, shows again the basic unity of power and power relationships, in spite of the fact that writers like myself may, for convenience of exposition, divide it into elements, like this division into force, wealth, and persuasion.

Assuming that power relationships have the basic unity to which I have just referred, what is the relationship between such power and the security which I listed as one of the basic human needs? The link between these two has already been mentioned in my reference to the fact that most power relationships (but not all) have a subjective target: they are aimed at the will of the opposition.

Before we consider this relationship, we must confess that there are power relationships which are purely objective in their aims and seek nothing more than the physical destruction of the opponent. If an intruder suddenly appears in one’s bedroom at night, or if a hostile tribe suddenly invades another tribe’s territory with the aim of taking it over, the immediate aim of the offended party may go no further than the complete physical destruction of the intruder, and this, surely, will have no subjective goal involving submission or surrender. The reason for this is that there already exists a subjective relationship covering the situation. This is the recognition by both parties that the interloper is an intruder entering an area he has no right to enter. In most such situations the defender would prefer to force the intruder to withdraw rather than to have to destroy him with incidental risks to the defender as well. Such withdrawal would be a symbol of the subjective acquiescence or obedience to which I have referred. In the rare cases where the defender’s sole aim is the destruction of the intruder, this abandonment of the more frequent, and more complicated, situation is usually based on fear.

Leaving such unusual cases aside, the normal goal of power relationships or the application of power by one party against another is for the purpose of establishing a subjective change in the mind of the opponent: to subject his will to your power, as a common and rather inaccurate version of the situation sometimes expresses it. The reason for this aim lies in the very significant fact that all power situations have two aspects, an objective aspect and a subjective, psychological, aspect. In practice, we sometimes call the objective relationship “power” and the subjective aspect “law.” But the two are ordinarily inseparable, and security rests in the relationship between the two.

In any ordinary relationship between two persons, or two groups, there is usually the relationship itself as an objective entity and there is also their subjective idea of the relationship. Put in its simplest form, there is security only when both parties have a roughly similar subjective idea of the objective relationship, and such security will be stable only when their relatively similar picture of that situation is fairly close to the real factual relationship.

This probably sounds complicated, but it is really fairly simple. When two boys first come together, they have no idea of their relative power. Eventually, they will disagree about something, and this disagreement will be resolved in some fashion. They may fight each other, or they may simply square off to fight and one will yield, or one may simply intimidate the other by superior courage and moral force. In any case, if there is no outside interference, some kind of resolution will demonstrate to both what is their power relationship, that is, who is stronger. From that moment, their power relationship has the double aspect (1) the fact that one is stronger than the other, and (2) that each knows who is the stronger. From that day on, they may be good friends and live together without conflict, each knowing that, when an acute disagreement arises and the stronger insists, the weaker will yield. Within and around this double relationship, each has freedom to act as he wishes. It is this freedom of action within a framework of power relationships which are clear to all concerned that is security. The opinion which they share of their mutual power relationship is law, as the objective relationship which they recognize is fact. Law, in this sense, is a consensus, on the factual situation as held by the persons concerned with it.

This relatively simple situation has become fearfully complicated in modern times in regard to the relationships between states, but basically the situation is the same. There is an objective power situation, made more significant by the fact that the modern state is an organization of power, and there is a consensus of a subjective kind as to what this objective power relationship is. This consensus is the picture they have of their legal “rights” in relationship to each other. It is subjective, although it may be written down on paper in verbal symbols such as in a treaty. In that case, we have three parallel entities, of which the first (the real situation) and the third (the treaty) are objective, but the vital one, the second, the consensus, is subjective. Peace and stability are secure only so long as all three are similar, by the second and third reflecting, as closely as possible, the first.

From this situation two rules might be established:

- 1. Conflict arises when there is no longer a consensus regarding the real power situation, and the two parties, by acting on different subjective pictures of the objective situation, come into collision.

- 2. The purpose of such a conflict, arising from different pictures of the facts, is to demonstrate to both parties what the real power relationship is in order to reestablish a consensus on it.

The chief cause of conflict is that the real power relationships between two parties is always in process of change, while the consensus, or the treaty based on it, remains unchanged. All objective facts, including power, are constantly dynamic, changing year by year, or even moment by moment to some degree, while the subjective, legal, consensus changes only rarely and usually by abrupt and discontinuous stages, quite different from the continuous changes of power itself. Conflict arises when men act in the objective world, because they act upon the basis of their subjective pictures, or even upon their symbolic verbalizations of those pictures. In the objective world where men act, they are bound to act more or less in accord with their real power, and their pictures of their power relationships are bound to diverge as their power and their actions based upon it diverge. This leads to conflict unless their consensus can be reestablished. But it is very difficult to reestablish a common subjective picture until there has been an objective demonstration of what their real power relationship is in some mutually convincing fashion. This is what conflict does. In fact, conflict is a method of measuring power to achieve such a mutually convincing demonstration and thus to reestablish consensus and stability.

So long as men, or nations, have the same picture of the power relationships among them, their acts will not lead to conflict because any act which might do so will lead to a warning (like the growling of a bear at a blueberry bush) which will recall both parties to look again at their consensus and bring their action into accord with it, but, when the factual power situation changes (as it inevitably does), the realization of the changes will penetrate the minds of the parties to different degrees (and even in different directions) so that their subjective pictures will diverge from the previous consensus, and their resulting actions, based on such different pictures, will lead to collision and conflict. It is, of course, perfectly possible for the subjective pictures in the minds of either or both to change without reference to the objective power relation at all. This is much more likely in the present period when most persons’ ideas of power and of these relationships are increasingly unrealistic, because of the ordinary man’s limited actual experience of power today.

The whole situation is clearly applicable to the two boys I have mentioned. Suppose these boys, whose relative power, say at age eleven, was clear to both, with A stronger than B, were to meet only infrequently over the next four years. During that interval, B, formerly the weaker, might, by exercise and more rapid growth, become the stronger. When these two come together again at age fifteen, with B in fact stronger than A and with A still retaining, as his subjective picture of their relative strength, the now erroneous idea that he is stronger than B, a situation of potential conflict exists. In such a case, B, formerly weaker but now stronger, has no clear picture of their relative strengths, because while he knows he is stronger, he has no way of knowing what increase of strength has been achieved by A. Once they are together, some difference of opinion may give rise to conflict, commencing, perhaps, with a simple effort of one to push the other from a doorway or pull him from a chair. As this test of strength develops and B discovers, perhaps to his surprise, his new ability to stand up to A, the latter, resenting this refusal of A to accept the older picture of their relationship, strikes out, and conflict begins. When it ends, it has demonstrated to both the true facts of their relative power (that is why it ends) and, by making this clear to both, has created a new consensus which becomes the basis of peaceful life together in the future.

Unfortunately this kind of fighting between young boys now occurs much more rarely than it did before (say a century ago) with the result that boys of today grow up to manhood and go off to fight, or to run the State Department, without any conception of the real nature of power and its relationships. This lack is, at the same time, one of the causes of juvenile delinquency and of adults’ mistaken belief that the role of war is the total destruction, or the unconditional surrender, of one’s opponent, instead of being what war really is, a method of measuring relative power so that they can live together in peace.

The role of any conflict, including war, is to measure a power relationship so that a consensus, that is a legal relationship, may be established. War cannot be abolished either by renouncing it or by disarming, unless some other method of measuring power relationships in a fashion convincing to all concerned is set up. And this surely cannot be done by putting more than a hundred factually unequal states into a world assembly where they are legally equal. This kind of nonsense could be accepted only by people who have been personally so remote from real power situations all their pampered, well-protected lives that they do not even recognize the existence of the power structures in which they have lived and which, by protecting them, have prevented them from being exposed to conflict sufficiently to come to know the nature of real power.

To this point we have discussed power relationships in a simplified way, as relationships between two actors, and have introduced only briefly complications which can arise from three other influences (1) the triple basis of power in our culture [i.e., force, wealth, persuasion]; (2) the dual nature (objective and subjective) of power situations; and (3) the changes which time may make to either side of power’s dual nature. Now we must turn to other sources of complication in power relationships: (4) the changes which space may make in power relationships; and (5) the fact that most power relationships are multilateral and not simply dual.

The influence which distance has upon power is perfectly obvious and may be stated as a simple law that distance decreases the effectiveness of the application of power. While no rule exists regarding the rate of such a decrease, it must be understood that the decrease is out of all proportion to the increase in distance and might be judged, in a rough fashion, to operated, like gravity, light, or magnetic attraction, inversely as the square of the distance. Thus, if the distance between two centers of power is doubled, their effective ability to apply their power against one another is reduced to one-quarter.

This example, which is given simply as an illustration and not as a rule or law, is made somewhat unrealistic by the fact that it assumes that the increased distance between two centers of power is of a homogenous nature without discontinuities or intrusive obstacles. But of course all distances in the real world are full of discontinuities and obstacles. A simple wall between two power groups may reduce the effectiveness of the application of their power to near zero. The two boys whom we have mentioned as coming together after an absence (which is the distance in space as well as time) of four years find their previous consensus about their power relationship is now unreal because their remoteness from one another in space over that interval made it impossible for them to observe each other’s changes in power. If, when they come together and begin to clash, some adult steps between them to suspend the conflict, or one of them slips into a house and slams the door, the intrusive adult or door becomes an obstacle to the application of their power and thus prevents the measurement of their power relationship. In fact, the two possibilities I have given are not the same. The door presents a case of the reduction of power by a discontinuity in space, while the interfering adult is an example of the introduction into a dual power relationship of a third power entity (which is factor 5 above rather than factor 4).

Space with all its discontinuities is, of course, one of the chief elements in any power situation and is blatantly obvious in relationships between states. The English Channel, as a discontinuity in the space between Hitler’s power and England’s power in 1940, became one of the chief elements in the whole history of German power in the twentieth century. Anyone who examines this situation carefully can hardly fail to conclude that Hitler’s attack on the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941 was a consequence of the existence of the English Channel which made it impossible for him to apply his power to England directly. The decision to attack Russia was based on Hitler’s judgment that, for his power, the distance to London was shorter by way of Moscow than it was by way of the Channel. Napoleon had made the same decision in 1812.

The usual discontinuities in space which reduce the application of power drastically are usually accidents of terrain (such as mountains, deserts, swamps, or forests) or the discontinuity of water. However, simple distance, as found in the Soviet Union or China, or as seen in the two oceans which shield the United States, reduce the ability to apply power rapidly. Nor should we mimimize the role which a simple wall may play in reducing the application of power. Hannibal wandered freely over Italy for fifteen years after the battle of Cannae (216 B.C.) but could not defeat Rome because he found the walls of the city of Rome impenetrable. And the period of European history after 1000 A.D. was dominated, on the power side, by the role of the castle wall, which fragmented power in Europe into numerous small areas and decentralized it so completely that it became almost purely local and private.

We should be equally aware of the fact that the damping role which space and its discontinuities have on power may be reduced by human actions in improving communications and transportation. These elements will be considered in the next section.

The role which distance plays in security rests on the two problems of the amount by which power is reduced by distance and by human judgments in respect to this amount. For example, if, in 1941, the power of the United States in Omaha was 100, and the power of Japan in Tokyo was 60, and the techniques of both for dealing with distance were the same, there was a point, or line, between them where their ability to apply power was equal. Since we have assumed that their rates of decrease of power over distance were the same, the line of equal power would have been much closer to Japan than to the United States. Let us say that it would have been somewhere along the 165th meridian. If their power was equal along that line, Japanese power would have been greater west of it and American power would have been greater east of it. We are speaking here of the facts of power, that is of the ability of each to mobilize more power than the other on its side of the line. If both governments were aware of the situation, there should have been peace and security for both, since Japan would not have insisted on the United Staes doing anything east of the line, and the United States should not have insisted on Japan doing anything west of the line.

This was, indeed, the situation between these two countries from about the end of 1922 until about 1940, because the Washington Conference of 1922 had fixed the relationship between the two in terms of capital ships, aircraft carriers, and naval bases so that the power of each fleet in its home waters was superior to the other. This situation was modified in the late 1930s by changes in naval technology, especially the development of fleet tankers, refueling at sea, and the range of both vessels and aircraft, but it was still true in 1941 that each was superior to the other in its own area. The American demand that the Japanese break off their attack on China, the American protectorate over the Philippines, the Japanese decision to take over Malaya and the Dutch Indies, and the Japanese sneak attack on Hawaii, were probably all in violation of the existing power relationship between these two countries in 1941, with the situation made much more uncertain by the fact that British, French, and Dutch contributions to the stability of the Far East had been neutralized by the Nazi conquest of Europe in 1940. From the change and uncertainty came the conflict of 1941-1945 in which the power of Japan and the United States was measured to determine which would prevail and to make possible the reestablishment of a new subjective consensus and a new stable political relationship based upon that.

The last major influence which complicates power relationships arises from the fact that such power relationships rarely exist in isolation between two powers but are usually multilateral. The complication rests on the fact that in such relationships among three or more powers, one of them may change the existing power situation by shifting its power from one side to the other. Of course such shifts rarely occur suddenly because the application of power in international affairs is rarely based on mere whim; and, insofar as it is based on more long-term motivations, changes can be observed and anticipated. Moreover, a system involving only three states is itself unusual, and any shift by one power in a three-power balance will usually call forth counter-balancing changes by fourth or other powers tending to restore the balance.

Such multilateral systems explain the continued existence of smaller states whose existence could never be explained in any dual system in which they would seem to be included entirely in the power area of an adjacent great power. The independence of the Low Countries cannot be explained in terms of any dual relationship, as, for example, between Belgium and Germany, since Belgium alone would not have the power to justify its continued existence within the German power sphere. But, of course, Belgium never had to defend its existence in any dual struggle with any one of its three great neighbors. It could always count on the support of at least one of them, and probably two, against any threat to its independence from the third. That means that any threat to the independence of Belgium would bring into existence a power coalition sufficient to preserve its freedom. And that is why the Netherlands, which had become part of the Spanish Habsburg territory by inheritance early in the sixteenth century, obtained its independence late in the same century and has preserved it since, against attacks from Spain, Louis XIV, Napoleon, Kaiser Wilhelm, and Hitler.

These same considerations apply to the independence of Switzerland, balanced between German, French, Austrian, and Italian power, but with the added consideration that Swiss terrain serves to reduce the effective power of any potential attacker, so that Swiss power itself may play a significant role in maintaining Swiss independence, without constant challenges. The Scandinavian countries are in a situation like that of Switzerland, with Britain, Germany, Russia, France and others balancing to create an interstice in a power nexus where they may survive. The obstacles of terrain, plus great power influence, also serve to balance the Scandinavian countries among each other within the other, larger, power system.

Of course if the three or more balancing great powers which preserve the independence of lesser states by their interactions were to reach an agreement on the division of these lesser states, the latter would pass out of existence, probably without conflict. We can see clear examples of this in the history of Poland, where tripartite agreements of 1772, 1792, and 1795 among Prussia, Russia, and Austria ended the independence of Poland. Poland was restored in 1918 because of the unlikely arrival of a situation in which Germany and Russia, fighting each other with power much greater than Poland’s, over Polish territory, were both defeated, and more remote states (France, Britain, the United States, Belgium, and others), whose powers contributed to this defeat of both Poland’s neighbors, used their temporary superiority in Eastern Europe to recreate Poland, without any consideration for the future real power situation in that area. As a result, the new state continued for only twenty years in a precarious and unstable balance in which continued support from the Western powers which had recreated Poland was so remote and thus weak that Poland continued to survive only from the temporary weakness of Germany and the Soviet Union and their enmity, which applied their power in opposite directions, thus creating a power interstice in which Poland could continue to exist only so long as these two did not reach any agreement to destroy it. Once they reached such an agreement, as they did in August 1939, Poland was doomed, since the events of 1938 had shown that French and British power in Eastern Europe was also neutralized to a point where they were unable to preserve Poland in the face of any Soviet-German agreement to destroy it. And Poland could be restored, as a satellite rather than an independent state, only when the Soviet-German agreement in Eastern Europe broke down into open conflict again.

In any actual power situation, all the factors I have mentioned play roles in producing the events of history. We can see an excellent example of this in the history of Turkish power in Eastern Europe. That history can be divided into four periods over a total duration of six or seven centuries. The first and third of these periods, covering roughly about 1325-1600 and 1770-1922, were periods of war and political instability, because in both, Turkish power was different in law from what it was in fact. In the second and fourth periods, covering about 1600-1770 and since 1922, there was relative stability because Turkish power was about as extensive as the area recognized as Turkish territory in the international consensus and legal documents. In the first period of instability, Turkish power was greater and wider than was recognized by legal provisions, and the Turks were struggling to obtain such wider recognition. This explains the constant wars in which the Turks sought to demonstrate that their version of their power was correct. As soon as the Turks were able to show (and obtain recognition that they had shown) that their power was greater than any other, not only in the lower Balkans, but also in the upper Balkans and even in Hungary, although they were not able to hold Austria or capture Vienna, it was possible to reach a rough agreement to this effect, and the second period, one of relative peace and stability, began. But Turkish power began to decay even more rapidly than it had risen, and, from 1770 onward the Turks had legal claims to areas where, in fact, they no longer could exercise their will. As a result, once again there was a disparity between their real power and their legal rights, although now in the opposite direction, with their legal position wider than their actual power. From this came the third period of their history, one of great instability and war, as the powers concerned tried to discover what was the real power situation in the south-eastern Europe. This became almost the most acute problem in European international affairs, known as “the Eastern Question.” It was the chief cause of Europe’s wars, including such events as the Greek Revolution of the 1820s, the Crimean War of 1854-1856, the Russo-Turkish war of 1877, the Tripoli War of 1911, the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913, and the First World War of 1914. It also gave rise to innumerable diplomatic crises, such as that of 1840 over Egypt, the Congress of Berlin of 1878, the Bulgarian crisis of 1885, the Bosnian crisis of 1908, and many episodes involving the question of which powers would replace the nominal suzerainty of the Sultan in North Africa.

The fourth period of Turkish history, since 1922, has been on in which Turkey has been a force of peace and stability in its area, because, once again, its area of legal power has coincided with its area of real power. This would not have been true if the Treaty of Sevres, imposed on the Sultan at then end of World War I, had been permitted to stand, because that treaty reduced the area of Turkish legal power to more restricted limits than the real Turkish ability to rule. If it had not been replaced by the more lenient Treaty of Lausanne in 1922, Turkish instability would have continued. Fortunately, the Turkish nationalists challenged the Treaty of Sevres and were able to prove that their power was wider than the area conceded to them by that earlier document.

A similar analysis could be made of the international position of the Habsburg Empire in the nineteenth century. In fact, the whole history of European international relations in that century could be written around three sharp divergences between power and law. These would center on the Ottoman and Habsburg empires and on the rise of Prussia to become the German Empire. In the first two the area of legal power was wider than the area of factual power, while in the third the opposite was true.

In all such crises of political instability, we can see the operations of the factors I have enumerated. These are (1) the dichotomy between the objective facts and subjective ideas of power situations; (2) the nature of objective power as a synthesis of force, wealth, and ideology in our cultural tradition and (3) the complication of these operations as a consequence of changes resulting from time, from distance, and from a multiplicity of power centers.

⤴️RETURN TO TOP

3. The Elements of Power

As we have said, war is a method of measuring power, and it is continued until the adversaries agree as to what their power relationship is in a particular situation. War is the application of force against the organizational patterns of the opponent to reduce his ability to resist, until agreement can be reached. Since the real goal of military operations is agreement, all such operations are aimed, in the final analysis, at the opponent’s mind, or rather at his will, and not at his material resources or even at his life. This has long been recognized by military men, although it is a truth which has not spread very widely among the civilian population. Even among military men, the recent growth of elaborate mechanical instruments for applying power, and especially the growing influence of the advocates of air power in military thinking, has made war more impersonal and thus concealed the real aim of military operations, but to military theorists it has long been a maxim that “the goal of strategy is … to break the will of the enemy by military means.” The airplane crew or missile operators who concentrate on enemy installations as targets easily lose sight of the real target, the enemy’s will, behind those installations, but thousands of years of human history show the truth of the older maxim about the goal of strategy.

Parallel with our recent confusions about strategy have been equally unfortunate confusions about the relationship between wealth and force. The relationship between these two is essentially the relationship between potential and actual. Wealth is not power, although, given time enough, it may be possible to turn it into power. Economic power can determine the relationships between states only by operating within a framework of military power and, if necessary, by being transformed into military power itself. That is, potential power has to become actual power in order to determine the factual relationship between power units such as states. Thus this relationship is not determined by manpower, but by trained men; it is not established by steel output, but by weapons; it is not settled by energy production, but by explosives; not by scientists, but by technicians.

When economics was called “political economy” up to about 1840, it was recognized that the rules of economic life had to operate within a framework of a power structure. This was indicated at the time by the emphasis on the need for “domestic tranquility” and for international security as essentials of economic life. But when these political conditions became established and came to be taken for granted, political economy changed its name to “economics,” and everyone, in areas where these things were established, became confused about the true relationships. Only now, when disorder in our cities and threats from external foes are once again making life precarious, as it was before the 1830s, do we once again recognize national security and domestic tranquility as essential factors in economic life.

In the past century we have tended to assume that the richest states would be the most powerful ones, but it would be nearer the truth to say that the most secure and most powerful states will become the rich ones. We assumed, as late as 1941, that a rich state would win a war. This has never been true. Wealth as potential power becomes effective in power relationships, such as war, only to the degree that it becomes actual power, that is, military force. Merely as economic power it helps to win a war only potentially and actually hampers progress toward victory. We could almost say that wealth makes one less able to fight and more likely to be attacked. Throughout history poor nations have beaten rich ones again and again. Poor Assyria beat rich Babylonia; poor Rome beat rich Carthage; poor Macedonia beat rich Greece, after poor Sparta had beaten rich Athens; poor Prussia beat richer Austria and then beat richer France several times. Rich states throughout history have been able to defend their positions only if they saw the relationship between wealth and power and kept prepared or, if they were able when attacked to drag out the war so that they had the time to turn their wealth into actual military power. That is what happened in the two World Wars. In each case the victims of German aggression were able to win in the long run only because there was a long run. If the Germans had been able to overcome the English Channel, their victims would not have had time to build up their military power.

Thus we see that wealth in itself is not of great importance in international affairs. It must be turned into military power to be effective, but then it ceases to be wealth. Wealth turned into guns no longer is wealth. But guns can protect wealth.

Another aspect of this error is to be found in the belief that the factual relationship between states is something which can be bought. All through the period after 1919 this illusion played a major role in foreign policies. During World War II we believed that the support and cooperation of neutrals like Turkey, Spain, or even Vichy France could be bought. We have sent such states goods, bought their goods at high prices, and given them loans. All of this meant only so much as our actual power at the time could make it mean. These acts could win nations over to cooperate with us only to the degree that it is clear that we have the real power to enforce our desires. The subsidy which Great Britain gave to Romania in 1939 did not prevent that country from cooperating with Germany, for the simple reason that Germany had the power in that area to enforce Romanian cooperation and Britain did not.

Another example of this same error can be seen in the efforts of the League of Nations or the satisfied powers to compel obedience to their desires by economic sanctions without military sanctions, as against Italy in 1935. Many persons, even today, are eager to use economic warfare, but shrink from using military methods, without seeing that the former will be effective only to the degree that they are backed up by military power. Since 1945 the United States has given billions of dollars in such economic bribes to scores of states throughout the world without increasing our power or obtaining our desires or even winning good will, if that was what we wanted, to any significant degree. In fact, the old, and cynical, adage, “If you want to lose a friend, give him money” seems to operate in international relations as well as in personal ones.

Confusions such as these, and even worse confusion which mistook verbal legalisms, such as CENTO, SEATO, and even NATO, for power, could have arisen only in a period of remarkably untypical human experience. The nineteenth century from about 1830 to about 1940 was such a period. The failure to see the relationship between economics and power, like the confusions between law and power, could arise when people had security for so long that they came to accept security as part of the natural order like oxygen. The confusion is seen in laissez-faire in domestic life as well. In the feudal period or in the long mercantilistic period which followed, conditions of insecurity were close enough for all to see what the real nature of power was. But in the century before 1939, security, at least for the English-speaking peoples, became accepted, and the separation of political from economic life became possible because security was present. But at that time, as always, prosperity was based on resources and security, and both of these depended on power to get and to hold. In Western Europe, where laissez-faire was established for this reason, these truths could be ignored because the Western nations, especially the English-speakers, were expanding over such a wide area of far weaker peoples and there were, at first, so few of these expanding states, that they could continue to expand in relative peace with little inference with each other and with only minor conflicts. In fact, their conflicts with their African and Asiatic victims were hardly regarded as wars at all. But this expansion was firmly based on military superiority. The wars which did arise, such as the Opium War on China, the destruction of the American Indian (even when the weapon of destruction was whiskey or measles virus), the Sepoy Rebellion, the Zulu or Ashanti Wars, and such, were firmly based on the fundamental foundation of military superiority. In many cases this military superiority was so great that it did not have to be applied in battle. The native rulers yielded and allowed their own communities to be destroyed by the non-military weapons of Europe, such as its disease, commercial practices, and legal rules. From this arose the curious result that the English-speaking peoples were able to persuade themselves that they had not needed their military power at all. They spoke of “peaceful economic penetration of colonial areas” even when natives were dying by millions, as in China, from the innovations they had brought in. By “peaceful” they came to mean, not that weapons had not been used because European military power was so overwhelming, but that weapons had nothing to do with it. The perfect example of this is the opening of Japan to Western commerce by Perry over a century ago. Only to Americans did this appear as peaceful economic action; the Japanese knew then as we know now, that it was a conflict of power even if that did not become overt.

That pleasant situation in which economics conquered the world for the West did not last long, but long enough to mislead the West into the belief that economics could prevail in world politics independent of military power. By 1890 that period was passing: politics and economics began to come together again, in what the West called “imperialism.” This happened partly because some of the non-Europeans like the Japanese began to use political methods against European exploiters and their fellow exploited alike, but chiefly because the available colonial areas of the world became fewer, just as the numbers of the European exploiting states became more numerous, with Germany, Italy, and the United States being added to Britain, France, the Netherlands, and other earlier colonists. As a result, economics came increasingly to rely on armed force in the international scene, especially when the late arrivals, like Germany, openly took to armed force in order to compensate for the head start enjoyed by Britain and France. These latter, by that time quite befuddled about how they actually had taken over so much of the world, tried to compete with the new imperialists by economics alone. They even insisted that economic methods of expansion were the only morally acceptable methods, and that Germany and Italy were immoral for attempting to use the weapons which the earlier imperialists had either not had to use or had forgotten that they had used. It was hard for the Germans to believe that the British, who had won Hong Kong in 1842 by using the crudest of forceable methods, were not being hypocrites in 1911, when they were horrified at Germany sending a gunboat to Agadir to protect German commercial interests in Morocco. An event such as Agadir convinced many Germans that all British were hypocrites as it convinced many English that all Germans were aggressors.

In the same way in which misconceptions about the relationship of politics and economics came into international politics, similar misconceptions came into domestic life about the idea of laissez-faire. These underestimated the need for tranquility at home and the need for political power, including force, as a framework for business in the same way that a political basis for economic action was needed in the international field. These domestic errors included two beliefs: (1) the belief that there are eternal economic laws to which political activity must be subordinated; and (2) the belief that economic methods and especially economic inequality could function without regard to the power situation in the community. As one consequence of this, when Germany about 1937 was violating our economic “laws,” we felt that the Nazi regime would soon go bankrupt. I can recall Salvemini in 1936 tracing a graph of the Italian gold reserves as a steadily falling line from about the early 1930s until the date in 1935 when these figures ceased to be published and then, by extrapolation into the future, finding the date when Italy would have no more gold and the Mussolini regime would fall from power. As if any nation with power and resources needs an economic convention like gold to operate, even in a world which accepts such conventions.

In this confusion of misconceptions and errors arising from the nineteenth century, Americans led the world because Americans had been shielded from the realities of human life for generations. In the nineteenth century we were not only shielded from other powers by distance, but that distance consisted of the world’s two greatest oceans, with only backward states lacking navies on the farther shore of the Pacific and with the British fleet patrolling the waters of the Atlantic. And, to complete the picture of a paradisiacal unreality, the good conduct of the British fleet was guaranteed by the fact that we held Canada as a hostage for such good behavior because of the long, undefended Canadian border. Thus we had security without any real effort or expense of our own and without even recognizing that it depended upon the power of other states. Even today, the past role of the British fleet and of the Canadian hostage in our nineteenth century security is largely unrecognized and will even be denied as a historical fact when I mention it. But in that pleasant fool’s paradise, Americans developed their dangerously unrealistic ideas of the nature of human life and politics. Since security is necessary rather than important, it was, like air, taken for granted by Americans who put other things, especially economics, higher on their lists of priorities. Thus Americans were naive in their relations to power, a quality which is carried over into their personal lives by their overprotected childhoods.

The events of 1941 gave a rude jolt to American naiveté, but the effects of such jolts are such as to demonstrate the importance of power rather than to teach its nature. We now do recognize its importance but are still widely uninformed about its nature and modes of operation, a condition of ignorance which seems to be as deep among our recent Secretaries of State as among more humble citizens. For the achievement of a higher degree of wisdom on this subject there are few topics more enlightening than the history of weapons systems and tactics, with special reference to the influence that these have had on political life and the stability of political arrangements. Experience may be the best teacher, but its tuition is expensive, and, when life is too short, as it always is, to learn from the experience of one’s own life, we can learn best from the experience of earlier generations. All such experiences whether our own or those of our predecessors, yield their full lessons only after analysis, meditation, and discussion.

One thing we learn from experience with power is that force is effective in subjecting the will of one person or group to that of another person or group only in a specific situation. There can be no general subordination of wills, because, as situations change, the wills of both parties may change. A man who will continue to pay a share of his crops to a political superior may refuse to permit the rape of his daughter by that superior.

In any specific situation the ability of one party to impose its will on another is a function of five factors making up the element of force. These are (1) weapons; (2) the organization of the use of such weapons; (3) morale; (4) communications; and (5) transportation or logistics. The last two indicate the importance of distance, already mentioned, since no one can be made to obey or yield to force, unless orders can be conveyed to him, his subsequent behavior can be observed, and force can be applied through the distance involved to modify his behavior. This seems more obvious to us than it has been in history, because our recent experience has been with such efficient communications and transportation that we tend to forget that for much of human history it was almost impossible to know what was happening even a few miles away, and it was even more difficult to influence such happenings when they were known. As recently as two generations ago, events and even acute crises in Africa were usually settled one way or another before the home governments in Europe knew they had occurred.